Story

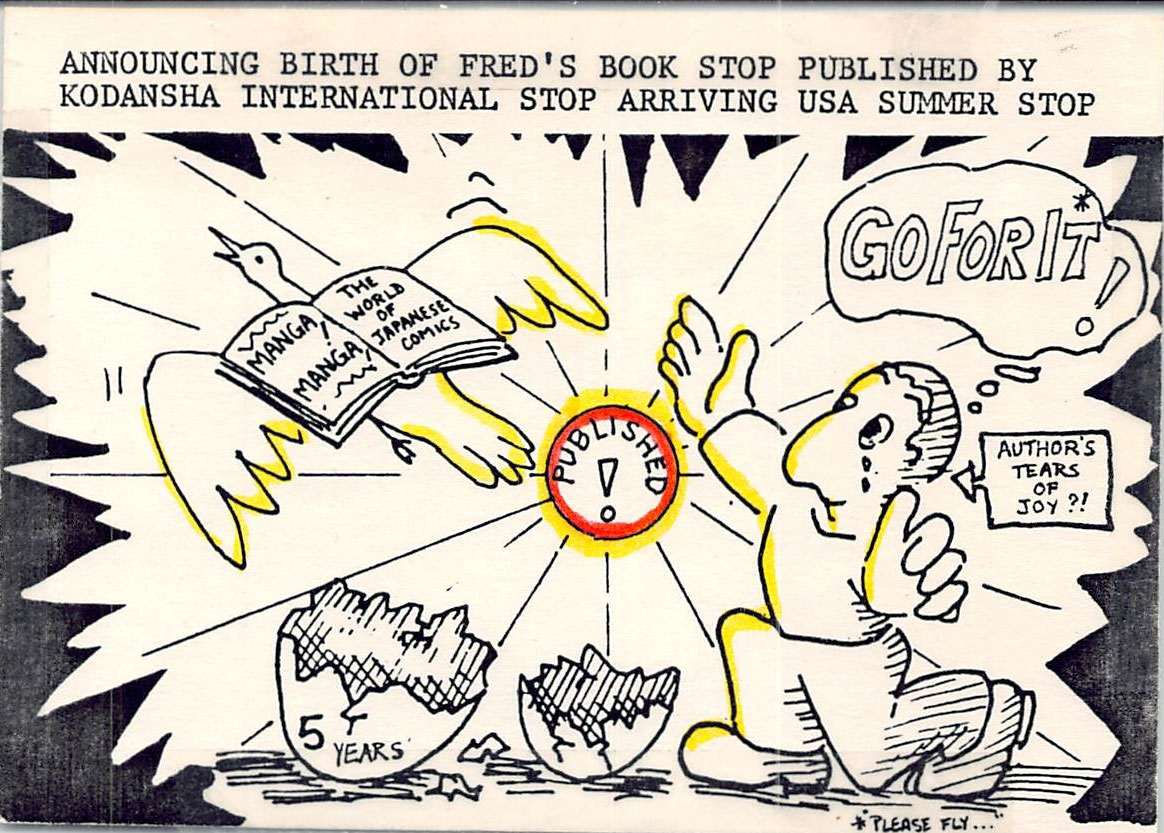

Manga! Manga! was published in 1983 by the late Tokyo-based publisher, Kodansha International. I wrote it mainly because I love manga, or Japanese comics, and I wanted to share my enthusiasm. At the time, I also felt the rest of the world was focusing too much on either Japanese management methods or the traditional triad of arts/crafts/zen, and ignoring the thriving and equally important popular culture of Japan. What follows is a short history of the book.

Around 1976-77, Shinji Sakamoto, Jared Cook, Midori Ueda, and I had put together a short-lived organization called Dadakai (駄々会), with the eventual goal of publishing manga in English for non-Japanese people to read. We translated a few works, but never had much luck getting to the publishing stage. In those days, of course, most non-Japanese had never heard of manga (and had probably never tried sushi, either). In retrospect, we were too ahead of our time. It therefore began to occur to me that, as a first step, the world might need a book about manga, before people would become interested in actually reading them, even in translation. A book, I hoped, might help to prepare the ground for later translations and publishing.

Sometime around 1977-78 I met with my friend Peter Goodman, who was also living in Tokyo. As he recalls it today, we met at a tonkatsuya, or fried pork cutlet shop, at the Yotsuya crossing, and I showed him a rough outline of what I was thinking. I had gotten to know Peter earlier when we were both studying at a university in Japan; I had gone on to work as a professional translator at Simul, in Tokyo, and he had begun working as an editor at the English-language Tokyo-based publisher, Tuttle. Nothing came of this initial meeting, as I recall (and it's no wonder, as my ideas were still in a very amorphous and primitive stage). We were also both still in our twenties. Soon after, Peter moved to London to do free-lance work for some British publishers and to manage a couple of projects for the Tokyo-based publisher Kodansha International (while hanging out in London with his Japanese artist girlfriend of the time). As for me, I left Tokyo and began living in San Francisco, doing translating, interpreting, and occasionally working as a production assistant for Japanese TV commercial film crews).

Around 1979 or 1980 Peter contacted me by letter from London. He asked if I were still interested in doing something with my idea, and when I said yes, he asked me if I would put together a proposal and a sample chapter, which he would submit to Kodansha International to see if it could be published. Kodansha International, or "K.I.," as it was affectiontely known, published high quality books on Japanese culture and Peter was about to go back to Japan to work for them full time. I created my proposal and a sample chapter about the history of manga, at great effort (heavily utilizing wonderful resources at the University of California's East Asian Library), and then I sent them off. This work later formed the core of the chapter "A Thousand Years of Manga"), but in retrospect, it wasn't very well done. Although I had once considered myself a good writer, years of studying Japanese and living overseas seemed to have dulled my English senses a bit; the initial prose was frankly quite awful. It was one thing to write papers for school, or to dabble in hippie-esque creative writing and poetry, but to create a non-fiction book for the world to read would require something on an entirely new level; I would have to relearn how to write.

The proposal eventually did get me a contract with K.I., but the path to it wasn't an easy one. I was terribly naive, and I travelled all the way to Tokyo at my own expense, optimistically expecting to quickly sign a contract in accordance with what I thought were certain pre-agreed terms and then to plunge into some serious research. On arrival, I found to my shock that the terms were not at all as I had understood them. This was my first book, and it didn't help that Peter, who had been my initial contact, was in London. In Tokyo, some of the terms I was offered would today probably seem outrageous (I was first told, for example, that the company didn't grant its authors copyright over their work, and often paid only around two percent in royalties). After some acrimonious barganing, and swallowing a few bitter pills, however, I signed, and started doing in-depth research in Japan. I wasn't doing it for the money, anyway, and it was more of an obsession. In retrospect, I have to say that there were also some huge advantages in working with K.I. Not only was I able to work with some excellent people, but in exchange for the harsh terms I got the parent company, Kodansha, to allow me access to their files and archives. Since Kodansha is one of the largest and oldest publishers of books and magazines (including manga) in Japan, it also has enormous clout in society at large. This fact also made it much easier to meet and interview many manga artists.

I made several trips to Japan to do research, staying there for lengthy periods, and I greatly enjoyed sleuthing around in libraries and archives, meeting publishers, printers, distributors, artists, managers, and fans, and trying to get as broad a view of the manga world as possible. I really threw myself into the work. I had to learn quite a bit about interviewing people, and about photography, especially how to shoot close-up macro shots of manga pages. In those pre-digital days, anything that would be printed in black and white had to be shot with black and white film, and anything that might be used in color had to be shot in color, so there was always a dilemma of what film stock to use, and it wasn't cheap. In one aspect, though, I was extremely lucky. For many people, including some famous artists, the idea that a foreigner would be even remotely interested in what was then thought to be such a "low-brow" medium as manga was a highly novel idea. They were quite excited, and often went out of their way to be helpful. I was also aided by the fact that I was already acquainted with Osamu Tezuka (手塚治虫)and along with my friend Jared Cook had been serving as his interpreter on his visits to the United States. Tezuka, Japan's "God of manga," was an enthusiastic supporter of my project, and he and his company aided me greatly in gaining access to other artists and the manga industry.

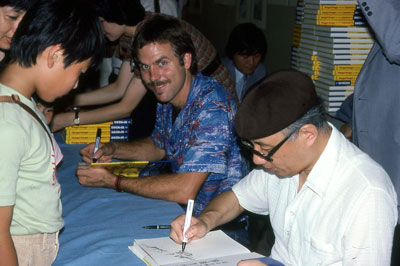

Perhaps because of his success with his Astro Boy animation series in the U.S. in the 1960s, Tezuka was then one of the few artists in Japan who was aware of the need to reach beyond a domestic audience. He later graciously agreed to write the foreword for my book, and when the book was first published he even held a special signing for me at a major Tokyo bookstore. People lined up outside the entrance, mainly to get Tezuka's autograph, and true to form he usually wound up not only signing, but drawing a wonderful illustration of his popular characters. And because of his presence huge stacks of the books were quickly sold—to scores of people who couldn't read English at all. At this one event, I think I sold more books than at any other event in my life.

I did the bulk of the writing for Manga! Manga! back at home in San Francisco. It was a struggle for me in many ways. As mentioned, my writing skills were more than a bit rusty. I remember showing one chapter to my girlfriend at the time and weeping in frustration when she told me it wasn't very good. Other friends also read my drafts and made suggestions, and I rewrote chapters over and over again. And this was all for the best. It is something I now do for all my books. Peter, who served as my editor, was in the beginning still in London, but he wrote letters (there being no email in those days), encouraging me and making many valuable suggestions about what to rewrite and what to cut. I still have a stack of letters that we sent back and forth, often with humor and interesting anecdotes. In retrospect, Peter was the sort of editor that doesn't exist today. Sort of my own personal Maxwell Perkins, the famous editor of many of the great American novelists of the 1920s and 30's. For Peter, I think, working on my book was also an opportunity to initiate a fun project in the company he had just joined, and to help create something new and perhaps important.

My writing process was very mid-twentieth century. It required quite a bit of physical effort. No one I knew had a computer then. I first wrote everything out in long-hand on yellow tablets. I was a self-taught typist, and not very good, but I painfully typed up my hand-written drafts on an IBM Selectric typewriter. I gradually learned that everything had to be rewritten many times, and rearranged, so I would type chapters up, then get down on the hardwood floor of my tiny apartment, and with a scissor and glue sticks do a literal and cut-and-paste routine, creating one very long continuous feed of edited paper. Then I would go back and type everything up again on new sheets of paper. And then repeat the process. Jack Kerouac is famous for typing his novel On the Road on one long sheet of paper during a three week period. I spent far, far longer than that, but I did work from long, assembled sheets of paper.

I tried to give a comprehensive overview of manga history and genres, so even if the reader didn't know anything about Japanese comics, it would be a great place to start. In the back I also included 96 pages of four translated long-arc manga excerpts to provide readers a direct manga experience. And these were also a lot of work. At the time, I was convinced that Americans would never be willing to read manga in their native original format, because it would require reading from the top right of the page to the bottom left corner, and turning pages from right-to-left. I thought that manga would have to be converted as much as possible to something resembling an American comic. So for the four selections, I tried to ask the artists in Japan to send me then-expensive mirror-image photostats of their art work. I erased the text in the word-balloons, often resizing the balloons and reshaping them to a more horizontal format. My friends Leonard Rifas (a comic book artist and publisher) and Linda Pettibone (a local graphic artist), helped me learn how to do comic book lettering, using the famous Ames guide tool and Rapidograph ink pens, so I was also able to render the translated text in the word balloons into American comicbook-style uppercase lettering. It may not have been top-notch professional lettering, but it was good enough. In many places I also modified the artistic Japanese sound effects on the pages, using white-out and drawing in my own versions, in English trying to maintain as much of the original flare of the Japanese characters as possible. Today, little of this work is necessary, as most American manga fans are now perfectly happy to read manga Japanese-style, from right to left ("backwards" from the English perspective), and they often prefer that Japanese manga "sound effects" be left as "art work," and given a tiny text footnote translation somewhere else on the page. I didn't know anyone who had a fax machine in those days, it was pre-FedEx, and there was a tight deadline. So when everything was done, I put the entire manuscript and art work in a box and went to the airport. There I met a courier I hired (at what then seemed a fortune) who hand-carried everything to the publisher in Tokyo.

At Kodansha International, the book was masterfully edited by Peter Goodman, and art direction was provided by Shigeo Katakura. Michiko Akamatsu (née Uchiyama) was of great help in securing illustrations and layouts. They were all employees of the company at the time, and for the company it was definitely something of a stretch, since most of their books were far more staid, and focused on traditional arts and crafts and more orthodox subjects. From what I have been told (and from looking at the result), those who did work on this book had a wonderful time, since at the time it was quite unusual, if not daring, subject matter, and even included some provocative illustrations. The foreword was written by none other than Osamu Tezuka, and it is interesting to read today, because he was entirely prophetic about manga's potential to cross borders and create a new kind of communication, even act as a sort of Esperanto, or international language. The blurb for the first edition was generously penned by Stan Lee, of Marvel Comics fame:

"COMICS! They're so much more than illustrated stories. They're a key to understanding a nation's people and its culture. Slashing samurai, gorgeous geisha, nefarious ninja, rambunctious robots, and much more....Congratulations to Frederik L. Schodt for introducing us to the wonderful world of Japanese comics in this beautiful book.

--Stan Lee

Soon after the book was published, writer Cat Yronwode also expressed what seemed to be a lot of people's opinions at the time: .

"If you really like comics as an art form--not just as a passive escapist vehicle for your jaded macho fantasy life--you will get a lot out of this book. It will amuse you, open your eyes to divergent cultural trends, educate you about how truly pouplar a pop medium can be if it is handled right, and it will probably send you off looking for a bookstore which sells Japanese comics." --Cat Yronwode in her ""Fit to Print," column in Comic Buyer's Guide, 1983-08-05.

It's interesting to look at the book title today. I actually wanted to use something along the lines of Japanese Comics, A New Visual Culture. I still remember discussing, almost arguing, about the title with Peter, my editor. He eventually persuaded me that we should use Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. Today, of course, most young people are very familiar with the term, manga, but at the time I feared in library card catalogs manga would be filed with "manganese" or confused with something to do with Italian cooking.

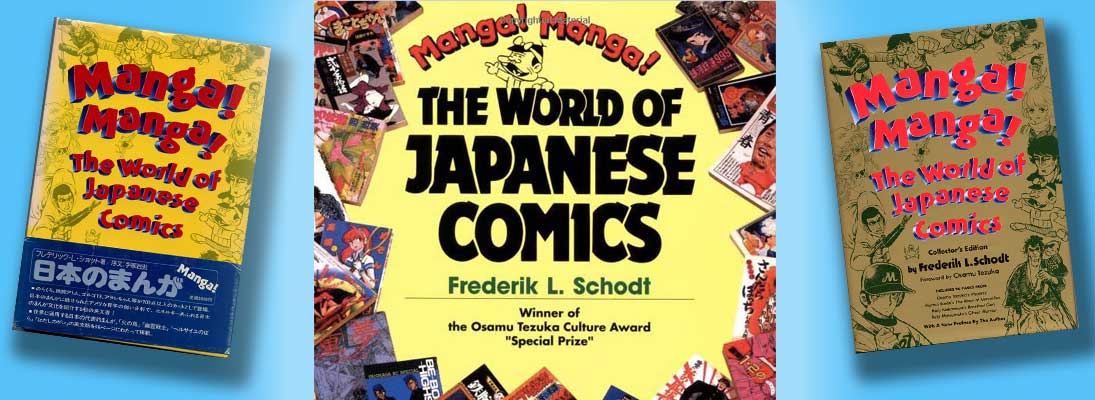

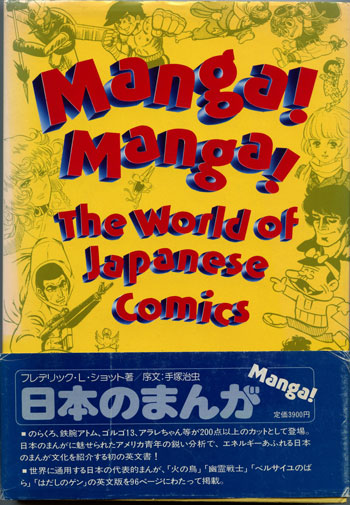

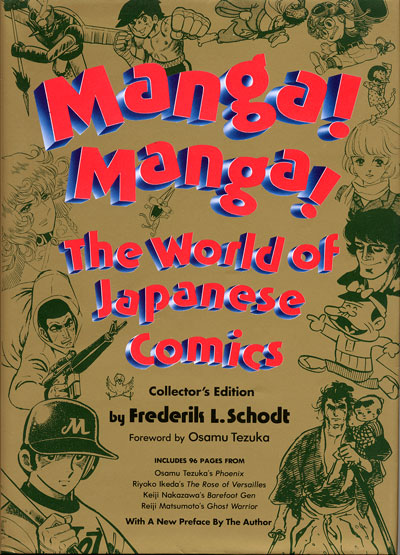

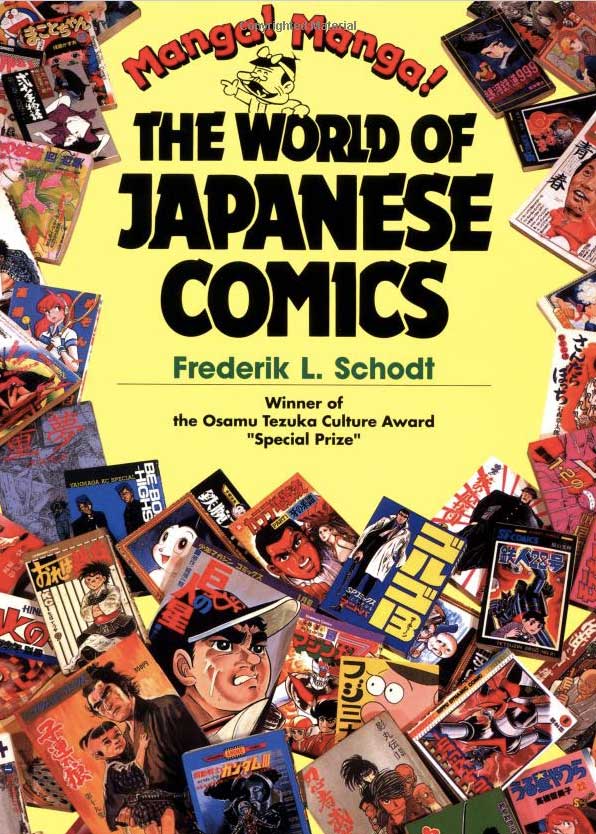

Although Manga! Manga! was first published as a hardback, it sold well-enough for KI to allow me to revise it slightly for a paperback edition in 1986. In 1998 Manga! Manga! was also reprinted with a new foreword by me, and a slightly tweaked cover (some new text on the back). The paperback edition is nearly identical to the original 1983 version. The hard cover edition was also beautifully reprinted as a "Collector's Edition" and came with a slightly different but very nice gold cover (replacing the former, bright yellow one). It is out of print today, and therefore a true "collector's edition." As the 1998 paperback blurb states:

"Since its publication in 1983, Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics has been the book to read for all those interested in Japanese comics. It is virtually a "bible" from which all studies and appreciation of manga begin. Moreover, given the influence of Japanese manga on animation and on American-produced comics as well, Manga! Manga! provides the background against which these other arts can be understood. A Collector's Edition is available for those who fully appreciate the value of the book and want an edition that aesthetically expresses that value.

Left 1983 Original HB || Right 1988 Deluxe HB

If this sounds boastful, please note that authors don't write book blurbs, publishers do! Also, it's important to point out that except for the new foreword by me and the slightly different covers, the 1998 editions are identical in content to the original 1983 one. The reasons for keeping the book in this pristine state are given in the 1998 foreword, and include the fact that Dreamland Japan, my 1996 book on manga, covers much of the newer developments in the industry, up to 1996. Manga! Manga! has gone out of stock many times in the past, and I was therefore extremely grateful for the publisher's decision to reprint it in 1998. Kodansha International's Michael Brase was particularly supportive in this regard and thus accrues eternal good karma.

Kodansha International, affectionately known as K.I., was a subsidiary of Kodansha Ltd, one of the largest publishers in Japan. It specialized in high quality English books about Japan, and its books helped greatly to increase knowledge of Japanese culture overseas. Unfortunately, in April, 2011, Kodansha International was closed by its parent company. This was truly a shock to the publishing industry in Japan, and, frankly, a tragic loss to Japan itself, especially given the role that the company played in helping to raise awareness of many fascinating aspects of Japanese culture among overseas audiences.

I often wonder, given the Japanese government's emphasis today on promoting Japanese culture—especially "Cool Japan"— if they really understood what the loss of Kodansha International meant. But I digress. While scores of wonderful books disappeared from circulation (to the eternal grief of their authors), Manga! Manga! was lucky. It was picked up by Kodansha USA, the New York-based arm of the parent company, Kodansha Ltd., and thus still remains in print today, forty years (!) after its initial publication. For those not familiar with the publishing world, most books are probably shredded by their publishers only a few years after they appear, so this makes Manga! Manga! quite a rarity.

--Back to top--Cover Text

"Manga means "comics" in Japanese. In Japan, manga are read by young and old and are a monster publishing phenomenon with annual sales in the billions of dollars. In the rest of the world, thanks to Japan's economic might, manga concepts are revolutionizing the toy, cartoon, and graphic design industries. Manga can be fantastical and funny, or gritty and violent, with heroes as diverse as samurai, sushi chefs, mah jongg masters, teenagers in love, and bored office workers, to say nothing of anthropomorphic cats and warrior robots. As such, manga offer an entertaining-- and sometimes disturbing-- window on Japanese society. Containing a historical overview, an examination of themes and artists, and over 200 illustrations from Japanese comics magazines, this classic work remains and essential guide for anyone interested in the future of popular visual culture. --From the back cover of the first 1983 edition.

"Since first published in 1983, Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics has been the book to read for all those interested in Japanese comics. It is virtually the "bible" from which all studies and appreciation of manga begins. More than that, given the influence of Japanese manga on animation and on American-produced comics as well, Manga! Manga! provides the background against which these other arts can be understood. The book includes 96 pages from Osamu Tezuka's Phoenix, Reiji Matsumoto's Ghost Warrior, Riyoko Ikeda's The Rose of Versailles, and Keiji Nakazawa's Barefoot Gen.From the back cover of the 2012 edition

Praise

W hen I wrote Manga! Manga! I never dreamed how popular manga would become outside of Japan. Today, I enjoy thinking now that my book has played a little role in manga's success. Certainly, it has never sold that many copies, but it has developed something of a cult following among manga aficionados around the world.

Amazingly, in the 1990s there was even a Japanese bistro in Berkeley, California, named after Manga! Manga!, where you could read manga while munching on sushi. Just like in Japan! In 1998, the anime/manga fan magazine, Manga Mania, described Manga! Manga! as " the book that just about every undergraduate and journalist in the country is ripping off," in a review stating that "After fifteen years of being plagiarised by lesser writers, Schodt's book is still effortlessly outshining them all." There may have been a little hyperbole at work in the prose, but a decade later, in 2008, on the website Comics Worth Reading, Johanna Draper Carlson would describe it as a "foundational must-read." More recently, In December, 2014, Ash Brown would describe it on the wonderful blog, Experiments in Manga, as, "a fantastic work. Even decades after it was first published it remains an informative and valuable study....Manga! Manga! is very highly recommended to anyone interested in learning more about manga, its history, its creators, or the manga industry as a whole."

Partly because manga were so unknown outside of Japan in 1983, when the book came out it was more widely reviewed and mentioned than anything I have written subsequently. In retrospect, 1983 may also have been a sort of "golden age" of traditional publishing, because there were still many magazines and newspapers that regularly ran reviews of books, and physical books probably played a larger role in society than they do today, when we are so drowning in free information from the web.

Here some comments from the early days, circa 1983.

"Phenomenal book...an exceptionally literate writer

--Cat Yronwode

"...a thoroughgoing exposition of the manga genre in text and pictures.

--The New Yorker

"An excellent historical guide to manga, as well as a fine introduction to various artists and major thematic concerns.

--Variety

"Buy this book. Read it.

--The Comics Buyer's Guide

More recently:

"Frederik L. Schodt’s groundbreaking Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics was one of the first, and remains one of the best, surveys of the history of manga and the manga industry available in English.

--Ash Brown, on "Experiments in Comics", December 2014.

"It’s rare that a seminal work should be the most comprehensive as well—and yet, twenty-eight years after its initial publication, it remains the best historical survey of manga available in English.

--Sean Michael Robinson on "Hooded Utilitarian", 2011.

"Frederik L. Schodt [is] one of the most referenced authors in the world by those who deal with manga, for his pioneering books Manga! Manga! [1983] and Dreamland Japan [1996]

--Marco Pelleteri, in The Dazzle and the Dragon, 2010.

"@debaoki: my pick for #booksthatchangedmyworld? hands down its manga manga! by @fschodt --it opened my eyes to a whole new world of comix.

--Deb Aoki, manga artist and critic/commentator, on Twitter, 06/16/2010

"It’s an excellent history of manga. It catalogues manga’s most important genres, creators, and characters. Fred Schodt really, really knows his stuff.

"It’s an excellent history of manga. It catalogues manga’s most important genres, creators, and characters. Fred Schodt really, really knows his stuff.

--Professor Susan J. Napier on "The Best Books on Manga and Anime," at Five Books, 2018.

When the book came out in 1983, it also won an award in Japan—the 2nd Japan Cartoonists Association's Manga Oscar, special award (日本漫画家協会オスカー賞, 特別賞). I think that today this is simply called the Japan Cartoonists Association's Manga Award, perhaps because of a conflict of interest with the Academy Awards in Hollywood. I unfortunately wasn't able to attend the ceremony, but my hero-editor, Peter Goodman, stood in for me, and was presented the award for the book by Shotaro Ishinomori, one of the judges (along with other manga luminaries such as Osamu Tezuka, Tetsuya Chiba Leiji Matsumoto, Keiko Takemiya, and Riyoko Ikeda). Here's also a photograph of the book displayed with the main Oscar award, in 1983.

The "special award" that the book actually received is a more muted bronze, but it still looks lovely on my shelf.

--Back to top--

Publishing Data

Paperback: 260 pages (including 96 pages of manga excerpts)

Publisher: Kodansha USA; Reprint edition (January 25, 2013)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1568364768

ISBN-13: 978-1568364766

Product Dimensions: 10.1 x 7.2 x 0.6 inches

Shipping Weight: 1.4 pounds

The current Kodansha USA edition of Manga! Manga! is identical to the 1998 K.I. paperback edition, except that the publisher is of course listed as Kodansha USA, and the address is now New York, and no longer Tokyo. Also, underneath my name on the front cover, it says, "Winner of the Osamu Tezuka Culture Award 'Special Prize.'"

Table of Contents

FOREWORD, by Osamu Tezuka

A THOUSAND MILLION MANGA:Themes and readers / Reading, and the structure of Narrative Comics / Why Japan?

- A THOUSAND YEARS OF MANGA: The Comic Art Tradition / Western styles / Safe and Unsafe Art / Comics and the War Machine / The Phoenix Becomes a Godzilla

- THE SPIRIT OF JAPAN: Paladins of the Past / Modern-Day Warriors / Samurai Sports

- FLOWERS AND DREAMS: Picture Poems / Women Artists Take Over / Sophisticated Ladies

- THE ECONOMIC ANIMAL AT WORK AND AT PLAY: Pride and Craftsmanship / Mr. Lifetime Salary-Man / Mah Jongg Wizards

- REGULATION VERSUS FANTASY: Is There Nothing Sacred? / Social and Legal Restraints / Erotic Comics

- THE COMIC INDUSTRY: Artists / Publishers / Profits

- THE FUTURE: The New Visual Generation / Challenges for the Industry / First Japan, Then the World?

- Osamu Tezuka's PHOENIX (Hi no Tori/「火の鳥」)

- Reiji Matsumoto's GHOST WARRIOR (Bourei Senshi・「亡霊戦士」, from the Senjou./「戦場」 series)

- Riyoko Ikeda's THE ROSE OF VERSAILLES (Berusaiyu no Bara/ 「ベルサイユのばら」)

- Keiji Nakazawa's BAREFOOT GEN (Hadashi no Gen/「はだしのゲン」)

- INDEX

- MORE ON JAPANESE COMICS

- LAST WORDS